|

Flamsteed Astronomy Society |

|

Did you know about... James Bradley and the Dragon’s Head? |

|

page 1 of 3 |

|

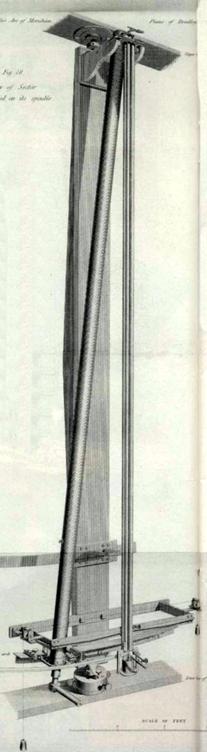

280 years ago, in 1724, James Bradley embarked on a programme of observation that would transform astronomy. In the south-west corner of the ROG Meridian Building, mounted opposite Halley’s Mural Quadrant, is an unassuming “piece of drain-pipe” which doesn’t get a second glance from most of the visitors to the ROG, but... James Bradley’s Zenith Sector (L) is arguably, with Airy’s Transit Circle, one of the two most influential instruments on display there. A zenith sector or telescope points almost vertically upwards to the zenith or point directly overhead.

Bradley got the right result for the wrong reason. To prove the Earth is in orbit around the Sun, he’d set-out to measure the apparent change of position of the star Gamma Draconis, expected due to the different viewpoints from the extreme positions of the Earth at each end of its orbit six months apart. Measurement of this annual ‘parallax’ would finally prove that the Earth was indeed orbiting the Sun. However, instead of measuring the apparent change of the star’s position due to parallax, Bradley stumbled onto the first direct evidence for the Earth’s motion through space round the Sun, an effect he called the aberration of light.

In 1725 Bradley, working with Samuel Molyneux, began observations of Gamma Draconis. Based on the direction of the star, Bradley expected its apparent position to shift due to parallax with the maximum displacements happening in December and June. The pair carried out a programme of 80 observations stretching into 1727 using Molyneux’s 24-foot zenith telescope in his Kew mansion. They found that the apparent position was indeed changing up to 20 arc-seconds each way on a 365-day cycle, but to their surprise the maximum displacements came not in December and June, but in March and September. Gamma Draconis, also known as Eltamin (which derives from Al Ras al Tinnen, “the Dragon’s Head”), was running three months late.

Molyneux was called away into the Admiralty and Bradley worked on alone. He couldn’t understand the meaning of the measurements and he needed to see if other stars were subject to the same effect. He had George Graham build him a new and better zenith telescope. Graham was London’s best craftsman and he’d made clocks and instruments for Halley at Greenwich. The 24-foot zenith sector at Kew was his work. Three years later, Graham was to give support and encouragement to John Harrison when Harrison came to London seeking the Longitude prize. At 12-feet, Bradley’s new zenith sector (the one now on display) was shorter than the Kew instrument but had a wider adjustment to allow Bradley to check more star positions. In August 1727 he installed it in his late uncle’s house at Wanstead and began work. Every star position he measured showed the same mysterious effect.

|

|

Bradley’s Zenith Sector 1727 © NMM |

|

James Bradley — 3rd Astronomer Royal © NMM |

|

Bradley scratched his head until Autumn 1728 (it was probably the wig that did it) when he had his ‘eureka’ moment. The story has it that he was taking a pleasure cruise in a sailing boat on the Thames. After a while he took to watching the burgee, the small flag at the masthead that was showing the wind direction. He noticed that every time the boat changed course, the wind direction shown by the flag also appeared to change. This was too much of a coincidence so he asked the crew about it. The sailors told Bradley that it wasn’t really a change in wind direction, but the flag’s behaviour was also affected by the boat’s course. A change in course would cause the flag to shift too. Bradley realised he was seeing the same effect through the zenith sector. The incoming starlight was equivalent to the wind, and the Earth’s motion was equivalent to the boat’s course. What he was measuring was affected both by the incoming light’s direction and by the Earth’s motion around the Sun. It was the sum of the vectors. He was having to tilt the telescope fractionally in the direction of the Earth’s motion to centre the star’s apparent position.

Bradley had directly detected the effect of the Earth’s motion around the Sun. Aristarchus, Copernicus and Galileo were vindicated: “eppur si muove” — and yet it does move; but... it was clear that all previous star catalogues, including Flamsteed’s, would need correction, and... he hadn’t managed to measure the annual parallax. The true dimensions of the universe remained unknown.

continued/ |

|

A07 |