|

Flamsteed Astronomy Society |

|

page 2 of 3 |

|

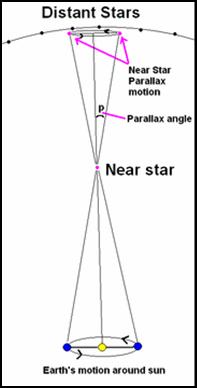

The measurement of parallax had been the Holy Grail of astronomers since the time of Aristarchus and Archimedes. If the Earth orbited round the Sun, as postulated by Aristarchus and formulated much later by Copernicus, then nearby stars should show some apparent change of position over an annual cycle because of the changed viewpoint from the Earth at each extreme of its orbit. This is the same effect as when nearby objects seen from the window of a moving train, appear to change position much faster than distant objects — ‘parallax’.

Unfortunately for Helio-centrists (notably Galileo), the best endeavours of astronomers for centuries had produced no reliable evidence whatsoever of stellar parallax — just as expected by the Geo-centrists: if the Earth was stationary at the centre of the universe then of course the stars would not show any change of position.

The best the Helio-centrists could do was to argue that the stars were so hugely distant that the parallax effect was tiny and beyond the ability of present instruments to detect. Succeeding generations worked to build better instruments and devise new strategies for measurement. Galileo explored two strategies: (1) Seen through a fixed telescope, the apparent track of a specific star as it transits the field of view should change after six months, and (2) the relative positions of two stars apparently close together, would change over six months, if one star was much more distant than the other (optical doubles) |

|

Hooke’s Zenith Telescope at Gresham College 1669 |

|

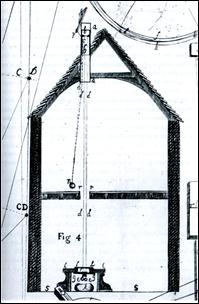

Flamsteed’s Well Telescope at Greenwich 1679 © NMM |

|

The formidable Robert Hooke was among the first to try and measure parallax using a fixed telescope. Hooke reasoned that a fixed scope pointed at the zenith could be aligned to the vertical with a plumb-line, and there would be no need to adjust the measurements for the refraction of light when it enters the atmosphere at an angle. It was Hooke who selected Gamma Draconis as a suitable target because it transits at the zenith at London and is bright enough to see in a scope in daytime. In 1669 he cut holes in the roof and floor of his apartments in Gresham College to mount a zenith telescope (L). Typically for Hooke, the design was ingenious, but also in fine Hooke style he made only four observations before moving on to other things. In the event he found all kinds of practical difficulties and the objective lens soon got broken (Aw, shucks!). Few were convinced by his pronouncement that the parallax of Gamma Draconis was 30 arc-seconds (more than 1000 times bigger than the modern value). |

|

Did you know about... James Bradley and the Dragon’s Head? |

|

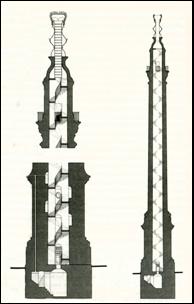

Design for The Monument to the Great Fire—Hooke/Wren 1676 |

|

Royal Observator John Flamsteed also got in on the act. In 1679 he had a well at Greenwich fitted with a spiral staircase and ’pineapple’ cupola roof so he could mount a zenith scope (L) up its 100 foot depth. Flamsteed soon gave up on account of the ‘damp of the place’ (and probably the spiders too). You can see the site of the well telescope behind the Meridian Building near Bradley’s Meridian. |

|

It would appear though that Hooke hadn’t completely given up. His design, with Wren, for the Monument to the Great Fire (R) had provision for a basement laboratory to exploit the column’s height, and included a zenith scope. The project came to naught. When the column was completed in 1676 he found there was too much vibration.

The scene was set for James Bradley

continued/ |