|

Flamsteed Astronomy Society |

|

Mapping the stars from antiquity to today — by Prof Nick Kanas MD March 29, 2010 |

|

page 1 of 2 |

|

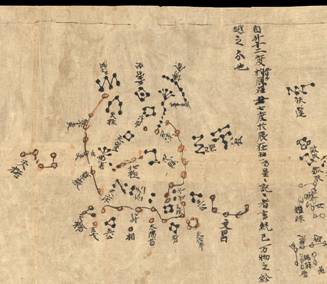

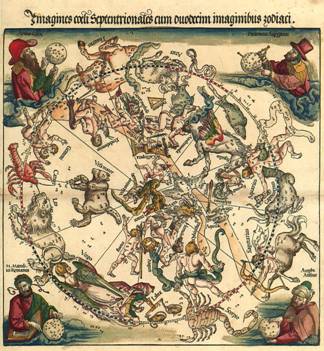

Nick Kanas is a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco. He’s been running a project with astronauts and cosmonauts about human interactions in space. Nick’s hobby and passion, though, is about mapping the stars and that’s why he came to speak to us at the Flamsteed. Nick says he’s been an amateur astronomer since he was 11 years old. He began before the days of computerised go-to scopes and he learned to ‘star hop’: finding a faint target by working from star to star guided by good old hardcopy star atlases. That’s when his interest in star maps began. He’s become a leading collector of antiquarian and all other kinds of interesting star maps and author of the book “ Star Maps: History, Artistry, and Cartography” Nick set the scene by talking about the different aspects of star mapping, including the spectacular (in many cases) artistry, and how celestial maps, like terrestrial, reflect the cultural and intellectual themes of their time. He talked us through the genesis of cataloguing and mapping the stars from antiquity, showing examples of ancient Chinese, Indian, and Egyptian systems and ‘maps’. The Chinese defined 284 constellations (star groups) needed to represent all the different aspects of their society which they believed reflected what was in the heavens. In time the Indian and Egyptian systems changed over to the Greek view exported by Alexander the Great. Nick traced the development of Greek astronomy from the Mesopotamians via ancient Egypt, resulting in the definition of the 48 classical constellations, including the signs of the Zodiac (all animals — the same word root as ‘zoo’ — except Libra) spread around the apparent annual path of the Sun through the stars: the ecliptic. Greek belief, from Hipparchos, Eratosthenes, and others, but enshrined mostly by Ptolemy of Alexandria in his ‘Almagest’, was passed on to the Islamic astronomers and then to medieval Europe. The earliest existing work is the Farnese Atlas, a marble sculpture of Atlas bearing the globe of stars on his shoulders, and dating from the 2nd century AD but thought to be a Roman copy of a Greek original from the 2nd century BC. The Islamic astronomers preserved and extended Ptolemy’s work adding star names (eg Algol), elements from their own Bedouin tradition, and mathematical refinement. Nick showed images from Al Sufi’s great work. In the Europe of the middle ages the mathematical foundation of Greek thought was lost and star images in manuscript on parchment, became illustrative representations. This approach was also continued at the start of the Renaissance with the first printed images. The details of Ptolemy’s system, however, had been preserved by the Muslims, exchanged with the Byzantines, and were disseminated through Europe after the fall of Constantinople in 1453. The earliest true star maps from Europe are from Durer (1515) and Piccolomini in his atlas of 1540 |

|

The Dunhuang Star Chart (British Library) |

|

Part of Durer’s chart 1515 |

|

Prof Nick Kanas [Pics Mike Dryland] |