|

[Pics Mike Dryland] |

|

Flamsteed Astronomy Society |

|

Mapping the stars from antiquity to today — by Prof Nick Kanas MD March 29, 2010 |

|

page 2 of 2 |

|

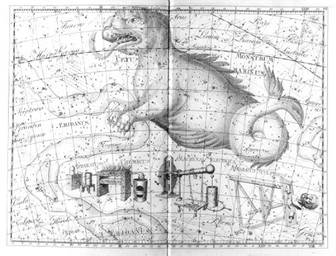

European astronomy began to flourish in the 17th Century reflected in the work of the ‘Big Four’ of star mapping: Bayer (Uranometria 1603), Hevelius (Uranographia 1687), Flamsteed (Atlas Coelestis 1729), and Bode (Uranographia 1801) — strangely, all these men had the first name ‘John’ (or local equivalent!). Nick showed a selection of the stunning images from this golden age. A rich profusion of constellation images is often coloured by hand later. Precision and grid systems developed quickly — Flamsteed charted 3,000 stars accurately as a basis for marine navigation; Bode charted 17,000 stars. Gaps in the knowledge of the southern stars, (invisible to the Greeks being below the horizon in Athens) were filled by the explorers then carefully charted by Halley and Lacaille. During this period constellations came and went — sometimes invented to please a patron (eg Halley’s ‘Robur Carolinum’ as a bootlick to King Charles II, and Bode’s nod to Frederick the Great). Nick honed our knowledge and appreciation by showing examples of ‘internal’ views of the constellations (as seen from Earth) contrasted with ‘external’’ or god’s eye view (reversed laterally, as if seen from outside the stellar system looking in at the surface of a globe). He also showed the progression from ecliptic-based grids where the ecliptic is the rim of a map (important to astrology), to those as now, based on the celestial equator and useful for telescopes. Bode’s 17,000 stars already made for an extremely complicated map with both stars and constellation images marked. As the age of the telescope progressed, more and more detail was crammed on to star maps. Soon we see the demise of constellation images on maps — they become just too cluttered. Later maps show subdued images, or just connecting lines in constellations, and then only constellation boundaries. Even the boundaries moved and varied from map to map until in 1922 the IAU agreed standard boundaries for the 88 modern constellations. Nick ended his engrossing talk with a review of the development of the modern star atlas, itself already a dying breed with the advent of computer control and ‘planetarium’ apps. Probably the most well-known modern atlas, Norton’s, was first published in 1910 with 6500 stars and 600 ‘nebulae’. Nick showed examples from Norton’s, Beevar’s (1948 1st), Tirion (1981), and the Millennium Atlas with 1 million stars. Originals from the golden age of the 17th and 18th Centuries may be mostly beyond the financial reach of new collectors now, but these final star atlases may be the new collector’s items of the future as the computer takes over! As in many things, we will miss the rich artistry of the past. MRD |

|

Nick & Gilbert Satterthwaite pursue a point Pic Mike Dryland |

|

Plate from Flamsteed’s Atlas Coelestis 1729 |

|

Plate from Bode’s Uranographia 1801 |

|

Nick’s book signing was popular Pic: Mike Dryland |